Professor John A. Douglass, University of California, Berkeley.

It is a malady of the modern age for universities. The forces of globalization and a campaign by various international university ranking enterprises place too much emphasis on a narrow model of what the best universities should be. One result: the notion of a “World Class University” (WCU) and the focus on its close relative, global rankings of universities, dominates the higher education policymaking of ministries and major universities throughout the globe.

Why the attention almost exclusively on research productivity and a few key markers of prestige, like Nobel Laureates? One major reason is that globally retrievable citation indexes (also a relatively new phenomenon) and information on research income are now readily available and not subject to the labor intensive, and sometimes dubious, efforts to request and get data from individual institutions.

But another reason is the sense that research productivity and prestige remains the key identifier of the best universities. The ancillary is that other primary missions of the most influential universities, such as high quality undergraduate and graduate education, a devotion to public service, universities as pathways for socio-economic mobility and regional economic development, are less important and, ultimately, harder to measure. Yet these are key activities that also require recognition, nurturing and expansion for top universities in Asia, in Europe, in Sweden, in the larger world. These are also among the strengths of Malmö University.

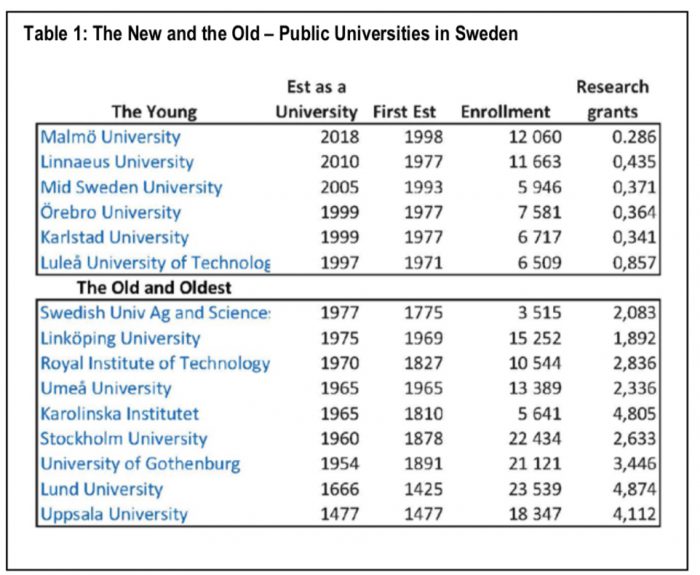

In its brief but increasingly spectacular existence, Malmö University has grown quickly since its establishment in 1998 on the southern tip of Sweden – a “blink of the eye” in terms of the often arduous process of developing quality academic programs.[1]

Its beginnings, and much of its current ethos, is that of a högskola, with an emphasis on less academic and more vocational programs such as teacher and nursing education, as well as technical education at the first-degree level. Now Malmö’s university is in the process of transitioning to an institution with a stronger emphasis on research (broadly defined), and new masters and doctoral programs, beginning in 2018.

There are strengths and weaknesses in Malmö’s högskola origins, one strength being a strong devotion to meeting regional education and labor needs. Many universities, and particularly those with great ambitions for rising in this or that global ranking, including putting less and less value in their role in regional focus research and economic engagement.

But in point of fact, most of the best universities in the world have their origins in geographically defined regional service. This is certainly true of all the major public universities in the U.S., including Berkeley, and it remains a central concept for its raison d’être. Despite the pull of globalism, geography still matters. Universities, in their various forms, are “anchor” institutions, tied to their location, and to the societies that gave, and give them, life and purpose.

The weakness in Malmö University’s short history is that its newer aspirations, including developing quality graduate education and expanding its research profile, and therefore financial resources, can often seem in contradiction with the practical focus of the högskola model. Faculty who have been hired to focus on teaching, for example, face growing expectations for producing research; graduate education implies greater integration and opportunities for research and public service.

One might see the transition granted by the Swedish government’s “full accreditation” of Malmö University, and rising expectations of stakeholders, from students to regional businesses and the local public sector, as extremely difficult and challenging. Indeed, the history of teaching-intensive universities transitioning to comprehensive and more research-intensive universities is a troubled one. Academic cultures, the expectation of government and others, the support services needed for students, and the financial model, have often clashed.

Yet, there is much reason to see the future of Malmö University as exciting and bright for three reasons. For one, Malmö University is young, and its rapid growth in the last ten years means a steady stream of new talent and, one would expect, openness to change and innovation. Since all but the Swedish universities in Uppsala and Lund also have their origins as högskolor, there are lessons to be learned from their transitions.

Two, the university’s existing role within the Malmö community, broadly defined, provides it with a unique identity. Malmö is the third largest city in Sweden, after Stockholm and Gothenburg, and the sixth largest city in Scandinavia, with a population of above 300,000. The Malmö Metropolitan Region is home to 700,000 people, and the Øresund Region, which includes Malmö, is home to 3.9 million people. Civic interest and support for Malmö University translates into financial and political support, including allowing for capital construction in the central part of the city.

And Three, and equally important, is the dynamism of the Malmö region, including the quality of life variables essential for attracting and retaining talent. A growing body of research suggests that quality of life (QOL), as well as access to locally accessible and regionally engaged universities, are becoming an increasingly important consideration in modern business location decisions, particularly for high–technology firms that are less tied to traditional location factors such as transportation costs, proximity to raw materials, and cheap labor.[2]

Noting all this, one may ask playfully, “what does Malmö University want to be when it grows up?” In the following, I briefly explore what it should not become, what it might become, and thoughts on a few key variables and pathways.

The pitfalls of the World Class University rhetoric

Isomorphism is all the rage. There is increased pressure for universities to pursue the model of the so-called “World Class University” (WCU) which, in reality, is defined simply as doing well in one or more global rankings of universities. These rankings, such as the Academic Ranking of World Universities (ARWU), focus almost entirely on measures of research productivity and a few key markers of prestige.

Many nations are pursuing higher education polices and funding schemes fixated on uplifting a selected group of national universities into the global ranking heavens. Sweden has not set a goal for having a designated number of universities reach the ranking heavens. But the WCU model, and rankings, remain a powerful influence.

In my view, the World Class rhetoric is not only hopelessly grounded in rankings, it is delusional for some and distracting and myopic for others – an incomplete thought that needs to be recognized for what it is: a fad. A powerful fad, to be sure. Not all of it is bad. One positive influence is promoting greater research productivity and eroding the civil service mentality of many academics. Another is increased funding for research. But can one say it has had much if any positive influence on the other vital responsibilities of universities?

At some point, universities need to espouse and embrace a larger vision of their raison d’être. And they need to do this in a powerful way that influences and shapes the ideas of their faculty and their ministries. Step one toward salvation: recognizing that the WCU rhetoric as inadequate, indeed, an old school idea of a university’s activities and priorities.

At this stage in its history, Malmö University’s origins and strategic planning efforts indicate that the WCU model is not a significant influence in its future development. Yet there are expectations, by the ministry, perhaps by some stakeholders, that it become a more significant producer of research, and competitive for research funding within Sweden, and within the EU and the Horizon 2020 program.

As a young institution, Malmö, and specifically its academic leadership and some faculty, may also be drawn to the gaming strategies that help in driving up citations and rankings: for example, a major impact of the global ranking regimes is devaluation of research and publications that are regionally relevant. But this would be a mistake.

Considering the New Flagship University Model

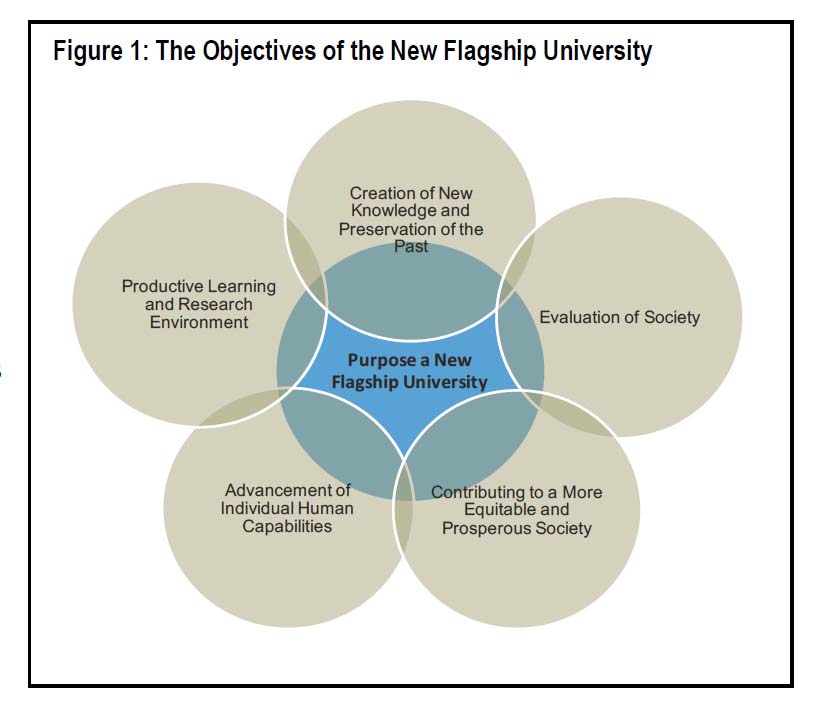

In an attempt to counter the WCU and ranking frenzy, which includes conferences and a growing cadre of consultants, I developed a more holistic and aspirational model that I call the New Flagship University.[3] The New Flagship moniker helps to stress that the most productive and engaged universities – those that seek societal relevance – are much more diverse and complex in the range of their activities and goals than at any other time in history.

Take almost any current public research university, and some non-profit private ones, and compare their sense of purpose, funding, programs, and expectations of stakeholders, with fifty or even twenty years ago, and they are very different.

The New Flagship model is also not a radical construct of the modern university: rather a reframing of the idea of the best and most engaged universities. The model is intended to provide pathways for universities to revisit and, in some instances, reshape their missions and academic cultures, to innovate, and to pursue organizational features intended to expand their relevance in the societies that give them life and purpose.

In this quest, international standards of excellence focused largely on research productivity are not ignored, but are framed as only one goal towards supporting a university’s productivity and larger social purpose—not as an end unto itself.

Figure 1 provides a general outline of the purpose of a Flagship University. This is simply my broad conceptualization of a university’s potential role in society. Universities may focus on one or more, reflecting the history, aspirations, and a clear-eyed understanding of its role as both a regional actor and a home for innovative thought and research.

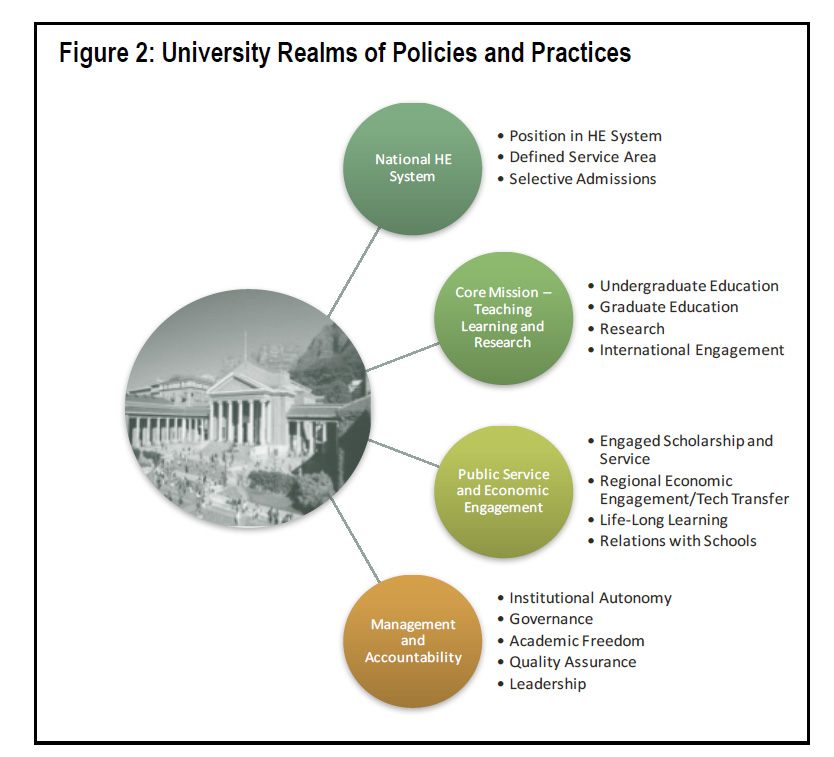

The Flagship model includes four realms of policies and practices derived in part by looking at the best practices of universities world-wide. This includes (1) its role in national systems of higher education, (2) its core missions of teaching, learning, research; (3) its public service activities and pursuit of various forms of economic engagement, and (4) its internal management and accountability practices (see Figure 2). Each relates to the institution’s external responsibilities and internal operations, and draws on examples of innovative activities in leading national universities from throughout the world.

Within the context of a larger national higher education system, the idea is that Flagship institutions have a set of goals, shared good practices, logics, and the resources to pursue them. To state the obvious, different nations and their universities operate in different environments, reflecting their own national cultures, politics, expectations, and the realities of their socioeconomic world.

At the same time, the purpose of the New Flagship model is not to create a single template or checklist, but an expansive array of characteristics and practices that connects a group of universities – again, an aspirational model. In my initial 2016 book, The New Flagship University: Changing the Paradigm from Global Ranking to National Relevancy (2016), I present a series of best practices and model programs to help illustrate the tremendous amount of innovation that many universities are pursuing.

A central characteristic of the New Flagship model, and the best universities, whatever their mission, is to support an academic culture that always seeks self-improvement – one that is both innovative and actively searching for best practices. This culture will not exist or come about by ministerial decrees for accountability, but by the internal policies and ethos of faculty and the larger academic community – an ecosystem extensively discussed in the model.

It is important to note that the New Flagship model is aspirational, intended to help inform universities that are or see themselves as comprehensive research-intensive institutions, or who are seeking a path to excelling in some aspects of the model. Hence, universities can also explore aspects of the model, and see where they are already highly active, and where they may want to further develop as they forge their own distinct character.

To state the obvious, not all universities are or should be comprehensive, or research intensive. In the immediate future, Malmö should avoid the trap of attempting to be a comprehensive university, with a full range of graduate and undergraduate programs, and the costs and institutional focus it requires.

In a selective use of the model, Malmö might conceive of itself as an Urban New Flagship University of its own design, focused specifically on academic degree programs, research, and targeted activities that support engagement and service to the Malmö region as it changes economically and socially. This is not to discount national, or even international service, but to place emphasis on the urban character of Malmö’s mission.

How specifically might this model inform Malmö University as it transitions its academic and professional programs to include more research, and more second and third cycle degree programs? How can it manage the rising expectations from stakeholders regarding its regional impact?

Before venturing on a few observations on the applicability of aspects of the New Flagship model, the following briefly discusses the strengths and weaknesses that face Malmö, from an outsider’s viewpoint.

Finding strength in Malmö University’s origins

The world is rapidly becoming more urban. Urban environments also pose great opportunities and complex challenges. “Urban universities are the next generation of great universities,” explains the mission statement of the Coalition of Urban Serving Universities, “with unique and central roles in our rapidly urbanizing world. They are models of inclusion and academic excellence, nimble and responsive with research and scholarship to address the challenges of our cities and societies and shape the future of our shared human community.”[4]

The Coalition also sees vibrant urban universities as anchor institutions, helping to create a virtuous cycle where “students and faculty are deeply engaged” with the local community and employers: “We are partners in prosperity.”

Again, Malmö University’s future, and its role in society, will be best served by remaining true in some measure to its urban and practical origins, and to current strengths.

This includes continued service to the regional area in the form of credentials and degree programs that meet socioeconomic mobility and labor needs, and research and public service programs that also focus on the university’s role as an “anchor” institution – an institution that supports other public and private entities and produces and draws talent to the area. Hence, Malmö already has three important strengths that provides it with a distinct identity):

- An academic and administrative culture that values urban/regional socioeconomic engagement.

- A vibrant city and regional economy that supports and understands the value the university brings to the region, and with its own set of challenges, including demographic change that will likely continue – this provides Malmo with its principal identity.

- A relatively high level of institutional autonomy that allows Malmö University to build its own academic culture and policies and practices to drive institutional development and strategic choices.

Yet it is also true, as noted, that Malmö University is an institution undergoing a transition, evolving into a more comprehensive institution that requires an expanded notion of its mission. Most significant is the expansion of third-cycle degree (doctoral) programs and increasing expectation of faculty to produce research and secure research grants – from the Swedish academy of science, the EU Research Council, or other sources.

In addition, seven of the 60 or so first-cycle degree programmes and approximately half of all second-cycle programmes are taught in English. There are other indicators of the transition that is unfolding. Initially, Malmö University enrolled almost all of its first-cycle students from the County of Skåne. In 2015, only 53 percent were from Skåne. More students are coming from other parts of Sweden, and there is a growing number of international students. At the same time, domestic Swedish students are increasingly diverse in their socioeconomic background. Some 30 percent have a non-Swedish background, reflecting changes in the region’s demographics.

There is also a shift in the funding environment for Malmö as well as all other tertiary institutions in Sweden toward performance based funding. As established by the Swedish Ministry responsible for higher education, and under legislation approved by the Riksdag, beginning in 2009, 10 percent of the funding and new resources are allocated on the basis of three quality indicators: publications, citations, and research funding from external sources. This has recently been raised to 20%, but is still at the margin of the national government funding for tertiary institutions, yet it sets new expectations.

Growth in research funding and scholarly publications, and graduate education, implies a potential shift away from the regional, urban university model that used to be Malmö raison d’être, and a shift in the role of faculty from primarily teachers, to researchers.

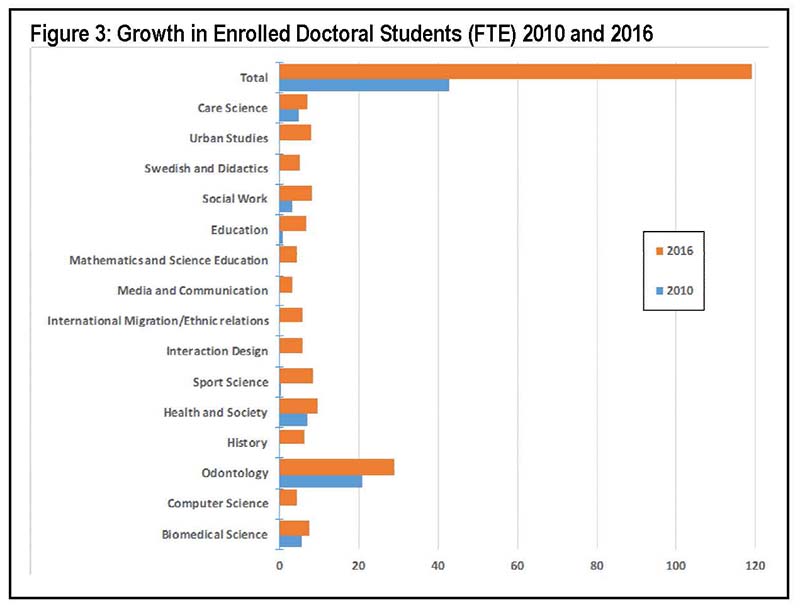

Figure 3 provides the increases in student enrollment in doctoral programs at Malmö. In 2010, there were only 42.7 FTE in doctoral programs offered by Malmö University, most in Odontology and related to Malmö’s acquisition of the School of Dentistry. However, a considerable number of doctoral candidates were employed by Malmö University but enrolled in programs at other universities. By 2016, many of these had transferred to new programs at Malmö and new candidates had been recruited, so that there were 119 FTE, with plans to grow in enrollment with the accreditation by the ministry. Most degree programs did not exist in 2010, and many, such as Urban Studies, Social Work, Sport Science, Education, Health and Society and Odontology, are professionally related programs – seemingly natural extensions of the university’s historical focus as what might be described as an urban polytechnic.

Developing and sustaining doctoral level programs that, in some manner, include research training, and more generally having a greater focus on research productivity, imply that the academic faculty at Malmö will be different in the future.

This includes the presumption of a changing mix in not only the number of disciplines that faculty have expertise in, but also a greater percentage of who have doctoral degrees and who have expertise in research methodologies and practice. Currently, only 60 percent of the academic staff at Malmö have doctorates, marginally higher than in 2012 when it was 57 percent.

At the core of any university is the quality and expertise of its faculty, and their understanding of their respective teaching, research, and public service roles. Expanding Malmö University’s mission should not mean losing its role as a primarily urban institution, but it will mean changes in the hiring and advancement practices of academic staff, but not toward a singular goal of hiring only good researchers, or only good teachers.

It requires a nuanced academic personnel system. It may also require strategic choices that other young universities have made to build their graduate and research programs, and sometime to help develop a more diversified academic faculty, including gender and ethnic diversity. This can include what are sometimes called “Target of Opportunity” programs that search for senior faculty with an expansive research portfolio and experience to help develop graduate programs.

In essence, Malmö University will need to make strategic choices, perhaps none more important than boosting the quality and innovative capability of its academic staff, and to further pursue policies and practices that build a culture of excellence and a sense of a vibrant community of students, academic staff, and administrators.

In the following, I briefly describe two policy areas outlined in the New Flagship model that are relevant to thinking about Malmö University’s present and future ambitions, and that relate to its stated goal to “strengthen the pivotal role of knowledge and science in society.” The first related to the ideas of engaged scholarship; the second, related to the importance of academic personnel policies that align with Malmö University’s stated mission.

Concepts of engaged scholarship and public service

As outlined in the New Flagship model, universities can promote public service in various forms by faculty, students, and staff via formal programs and incentives. This form of university “outreach” is extremely important, providing a significant impact on local and regional communities, opportunities for learning and experimentation, and direct evidence of a university’s priorities.

For example, universities, as one observer has stated, can focus “expertise on improving living conditions in poor areas that can make serious headway against social problems. As civic engagement elevates the quality of university teaching and learning, it produces millions of university graduates with both hands-on competence in their fields and a personal commitment to being agents of social change. And increasing public goodwill for universities can make government and private funders more generous in their financial support” (Hollister 2014).[5]

All leading national and urban based universities, and more specifically a subset of their students, faculty, and staff, are engaged in some form of public service. The question is the coherency of these efforts, and, just as importantly, the extent to which they are recognized, valued, and publicized within the institution.

Several factors help explain relatively high levels of engaged scholarship and public services in America’s leading public research universities. One is the expectation that students applying to universities at the undergraduate level have some public service experience, broadly defined. When they enter the most-selective universities, most American students already have substantial experience in student volunteerism and community engagement.

A second factor relates to expectations placed on faculty and an academic culture that has long valued community service and engagement with local business and governments – although with differences among the disciplines. This includes incorporating engaged scholarship into faculty reviews of performance and promotion. And a third factor: developing and nurturing campus organizations that are targeted toward community engagement. The following provides examples of how universities can pursue this central part of their mission.

Community Volunteering

Faculty, students, and staff at most universities interact informaly as individuals in various forms of community service. But Flagship universities should include formal mechanisms, such as “community service centers,” that attempt to identify and link the university community with opportunities for volunteer work. Various forms of civic engagement provide an important path for universities to contribute to local needs – in schools, in hospitals, local social services, charities, and similar community-based activities. It also raises the visibility, and the value, of the universities within their communities.

Service Learning

Beginning in the 1980s, universities in the United States developed the idea of “service learning” as a pedagogical approach, focused on student learning at the undergraduate and graduate levels through activities that benefit the community – a form of experiential education. Properly developed as a component of the curriculum, service learning can be transformational for students by both connecting them with their personal interests and expanding their understanding of their role in society. Today, service learning often includes credit-bearing courses for undergraduates and faculty-directed internships with a public service focus, similar programs for graduate students, and resources and support for faculty to generate their own initiatives.

The University of Michigan, for example, has an endowed center for engagement, focusing on student service learning and partnerships, and produces a peer-reviewed journal of scholarly work. Additionally, living and learning communities, honors, and other cohort curricular modules are focused on civic learning issues that promote student and faculty civic engagement with the issues of diversity, access, and student success.

Similarly, UCLA established the Center for Community Partnerships – a reflection of the high priority the campus has placed on engagement with its surrounding community in the Los Angeles area. This was not the beginning of UCLA’s involvement in the community; the university has been engaged in the Los Angeles area for decades, though not in a systematic way. The goal of the Center is to strategically guide UCLA’s public service activities.

Reflecting the importance of the service learning movement, over 1,100 colleges and university in the United States are part of the Campus Compact organization that shares best practices and innovations among universities. More recently, an international organization, the Talloires Network, has emerged with similar goals, promoting the concept of the “engaged university” as a core institutional mission – again, a relatively new concept for many universities. The following summarizes some of the goals and benefits of service learning related to students:

- Increase retention, particularly among first-generation college students.

- Increase diversity of local enrollment as a form of outreach.

- Enhance achievement of core learning goals that has an effect on progress to degree.

- Make learning more relevant to students, helping them clarify their talents and interests at an early stage of their academic careers; it often impacts choice of major and eventual career.

- Develop students’ social, civic, and leadership skills.

- Strengthen undergraduate research skills and capabilities.

- Encourage students to be productive participants in the community by connecting them to their surroundings.

Faculty-Engaged Policy Research

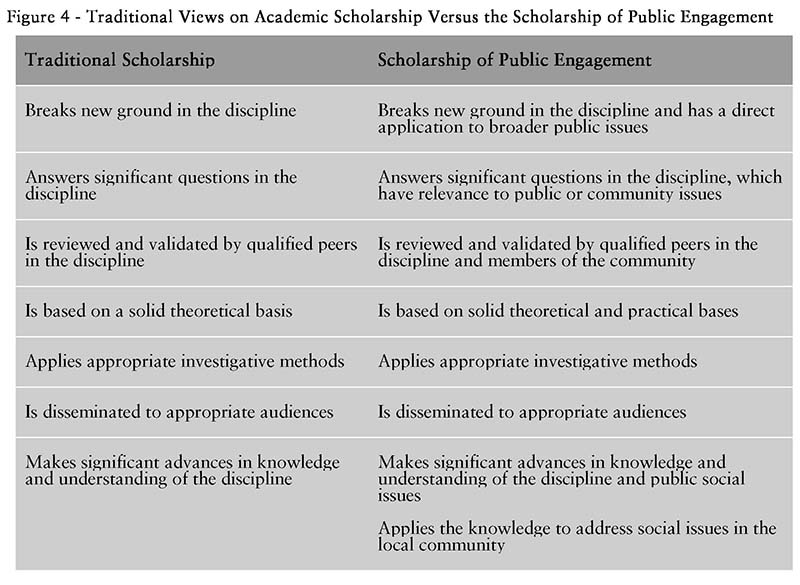

Flagship universities look for ways to encourage academically relevant work that simultaneously meets campus goals and community needs. In essence, it is a scholarly agenda that integrates community issues as a value for faculty. In this definition, community is broadly defined to include audiences external to the campus that are part of a collaborative process that contributes to the public good. Figure 4 provides a comparison of the traditional view of academic scholarship to scholarship that is publicly engaged. Both should have high value within the contemporary Flagship University.

The following summarizes some of the benefits that can be derived by a systematic approach to promoting and supporting engaged scholarship by faculty.

- Bolster the links between research and teaching. Research indicates that learning is enhanced by real-world experiences that broaden a student’s perspective and connect theory with practice. In addition, research that is informed by community participation can have a uniquely meaningful impact that is locally visible.

- Improve diversity, student retention, and progress to degree. A university that more fully integrates community engagement into its research and teaching develops stronger ties to multiple communities and may be better able to attract and engage a diverse student body. In addition, research shows that engaged students remain in school and progress to degree at a greater rate than students who are not engaged.

- Reenergize faculty around engaged scholarship. Creating a civic engagement initiative and providing a supportive infrastructure may reenergize faculty teaching and research by providing a fresh perspective on the value their work brings to society.

- Connect the university to policy makers. Universities are being questioned about their relevance, lack of transparency, and high costs. Community-based teaching and research is one way to “live” the public mission and reinforce the important role that the university plays in serving the public good.

- Build transdisciplinary and interdisciplinary research capacity. The problems of society are complex, and addressing them requires expertise and research that cross disciplinary lines. These capacities should be supported among faculty and nurtured in students.

- Building a research community around societies’ most challenging policy issues. Focusing on issues that are of local and national public concern brings the unique strengths of a research university to bear on the most pressing challenges that face the nation. This can enhance public knowledge of and appreciation for the university system, thereby making more tangible the return on public investment in higher education.

- Bringing in new resources and funding. Both government and private funders are calling for more collaborative approaches to projects as a condition of funding. In addition, local and regional funders who may not normally contribute to university endeavors may have greater interest in investing in projects with clear public purposes and applications.

- Build social capital among students, faculty, and communities. Academic inquiry not only addresses critical research questions but also enhances the ability of students, faculty, and communities to take action and build ongoing relationships that yield multiple benefits. The development of such social capital has been shown by research to strengthen communities, making them more resilient and healthy. New networks of trust and cooperation are likely to emerge and create academic partnerships for scholarly work.

Concepts relating to the role of faculty

As stated in a 2014 Centre for Business and Policy Studies (SNS) report, “Faculty recruitment and promotion processes at many Swedish departments are closed and still not transparent, leading to a large degree of staff being recruited from among PhDs from within the department, a behavior that stands in stark contrast to many of the leading universities.”

The report also noted that PhD students are regularly recruited from within the university and, often, the department from which they obtained their undergraduate degrees.” [6] Perhaps these patterns of faculty recruitment have begun to change since 2014 at Swedish universities. As Malmö University grows in the diversity of its academic programs, and in the number of doctoral students, it is important that it not regularly hire new faculty from the ranks of its Ph.D. recipients. Such a pattern of hiring creates an environment of entitlement and incestuousness, and diminishes the diversity of talent a university can acquire through a more open recruitment process.

Current and new faculty need clear outlines of expectations that help shape behaviors and advance the broad range of responsibilities of an institution, and that are based on a process of peer review – and not on a civil service structure which tends to value time in a job over performance.

How to evaluate faculty performance and promise? The following provides an overview that may be helpful to the academic leadership at Malmö University as it shapes its academic staff to align with increased expectations on faculty teaching, research and public service roles.

It is important to recognize considerable variation in the research interests of faculty – some pursue traditional forms of research and other “engaged scholarship.” Further, faculty teaching, research, and public service interests evolve over time.

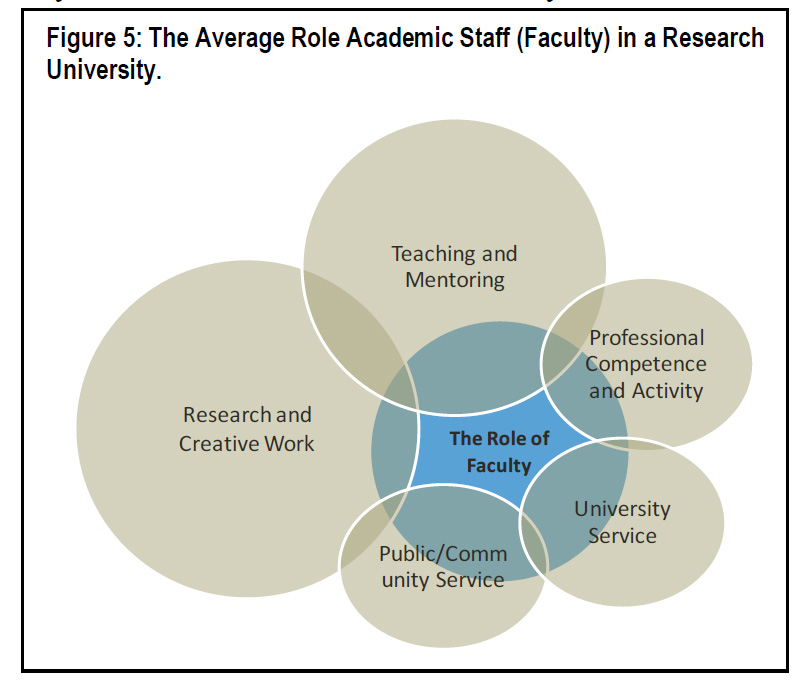

Again, based on the New Flagship model, Figure 5 provides a conceptualization of the primary areas of responsibility and activity for faculty in a research-intensive university: teaching and mentoring, research and creative work, professional competence and activity, university service (including activities related to academic management at the program, discipline, and campus-wide levels), and public/community service.

The size of each sphere is only an example of a faculty member with significant research productivity. Theoretically, the weighting will vary depending on faculty members’ interests, abilities, and stage in their academic careers.

Faculty Responsibilities

Again, a key factor for shaping Malmö University’s future will be the expectations placed on faculty to meet the university’s evolving mission. Based on this model shown in Figure 5, the following provides a sample of criteria for faculty appointment and advancement adopted from policies at the University of California (UC). This is simply an example, but also one that has had a powerful influence on the behaviors of faculty at UC:

- Teaching – Clearly demonstrated evidence of high quality in teaching is an essential criterion for appointment, advancement, or promotion that includes documentation of ability and diligence in the teaching role. In judging the effectiveness of a candidate’s teaching, peer review should consider such points as the following: the candidate’s command of the subject; continuous growth in the subject field; ability to organize material and to present it with force and logic; capacity to awaken in students an awareness of the relationship of the subject to other fields of knowledge; fostering of student independence and capability to reason; spirit and enthusiasm which vitalize the candidate’s learning and teaching; ability to arouse curiosity in beginning students, to encourage high standards, and to stimulate advanced students to creative work; personal attributes as they affect teaching and students; extent and skill of the candidate’s participation in the general guidance, mentoring, and advising of students; effectiveness in creating an academic environment that is open and encouraging to all students, including development of particularly effective strategies for the educational advancement of students in various underrepresented groups.

Attention is paid to the variety of demands placed on instructors by the types of teaching called for in various disciplines and at various levels, and should judge the total performance of the candidate with proper reference to assigned teaching responsibilities.

- Research and Creative Work – Evidence of a productive and creative mind should be sought in the candidate’s published research or recognized artistic production in original architectural or engineering designs, or the like. Publications in research and other creative accomplishment should be evaluated, not merely enumerated. There should be evidence that the candidate is continuously and effectively engaged in creative activity of high quality and significance. Work in progress should be assessed whenever possible. When published work in joint authorship (or other product of joint effort) is presented as evidence, it is the responsibility of the department chair to establish as clearly as possible the role of the candidate in the joint effort. It should be recognized that special cases of collaboration occur in the performing arts and that the contribution of a particular collaborator may not be readily discernible by those viewing the finished work.

- Professional Competence and Activity – In certain positions in the professional schools and colleges, such as architecture, business administration, dentistry, engineering, law, medicine, etc., a demonstrated distinction in the special competencies appropriate to the field and its characteristic activities should be recognized as a criterion for appointment or promotion. The candidate’s professional activities should be scrutinized for evidence of achievement and leadership in the field and of demonstrated progressiveness in the development or utilization of new approaches and techniques for the solution of professional problems, including those that specifically address the professional advancement of individuals in underrepresented groups in the candidate’s field.

- University and Public Service – The faculty plays an important role in the administration of the University and in the formulation of its policies. Recognition should therefore be given to scholars who prove themselves to be able administrators and who participate effectively and imaginatively in faculty government and the formulation of departmental, college, and university policies. Services by members of the faculty to the community, region, and nation, both in their special capacities as scholars and in areas beyond those special capacities when the work done is at a sufficiently high level and of sufficiently high quality, should likewise be recognized as evidence for promotion. Faculty service activities related to the improvement of elementary and secondary education represent one example of this kind of service.

Similarly, contributions to student welfare through service on student-faculty committees and as advisers to student organizations should be recognized as evidence, as should contributions furthering diversity and equal opportunity within the University through participation in such activities as recruitment, retention, and mentoring of scholars and students.

Again, not all faculty will or should perform all of these roles within a university. There are major differences among the disciplines, among academic and professional programs, and in the needs of students. And even within disciplines, individual faculty will and should vary in their interests and expertise.

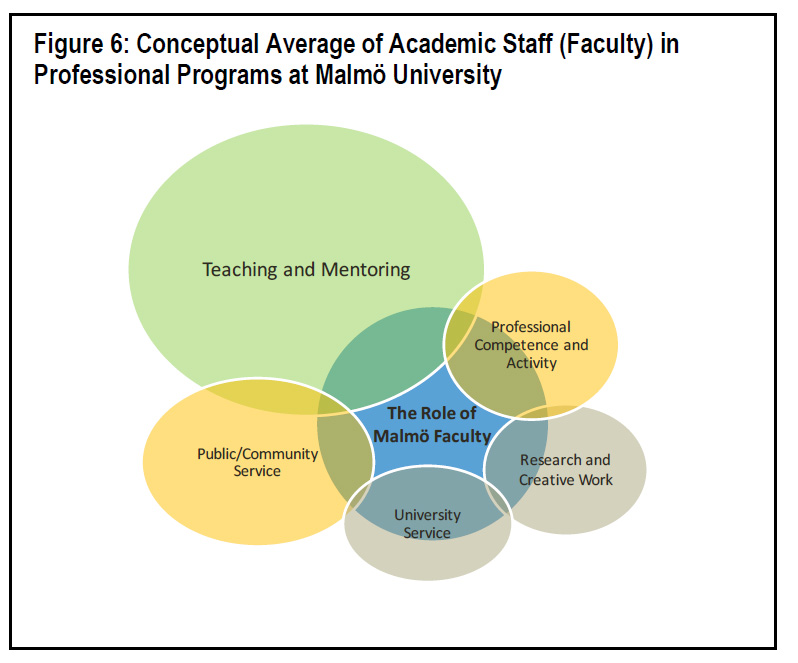

This broad concept of the role of academic staff simply offers a way to think about the articulating the expectations of faculty at Malmö University. To help illustrate this, we might suppose that faculty at Malmö, and in certain professional fields, could have a much stronger emphasis placed on teaching and mentoring, and professional activities. Figure 6 provides conceptual idea of this, with the size of each area of responsibility reflecting the level of effort and time spent.

Malmö as a vibrant urban university

Sweden, like other nations with postmodern economies, understands its growing dependence on “knowledge accumulation” and on the process of applying knowledge both in the marketplace and for social progress. Along with government and the private sector, universities play a pivotal role in building the productive regional and national ecosystems necessary for globally competitive economies. Universities in particular are significant actors both in creating new knowledge and for attracting and educating talented people.

In 2012, in order to help push Swedish universities to become more economically and socially engaged, the government established new incentives for its national universities to increase research and interaction with regional economies and to foster economic innovation and regional engagement.[7]

The 2014 study on Sweden’s own innovation system by Matts Benner et al noted earlier stated that “some current characteristics of the Swedish university system are suboptimal and risk becoming serious challenges for Swedish universities and for Sweden as the global research and education landscape changes.” They observe that, “Swedish universities are weakly organized, with a disjunction between teaching, research and interaction, with a strong tradition of internal recruitment, with unclear promotion patterns, with career paths heavily skewed towards research achievements, with a similarly skewed understanding of the meaning of ‘societal interaction,’ and with teaching environments that are not sufficiently attractive to compete at the top level internationally.”[8]

In addition, a 2016 study by Emily Wise, Sylvia Schwaag Serger and colleagues at Vinnova reported gains in how Swedish universities had become more integrated and important in regional economic development, but also identified a need for greater organizational effort to assess the impact of the nation’s universities on the communities they serve. To be economically competitive, there is also the reality that Sweden needs universities that are internationally attractive to talent. “Growing mobility, intensifying global competition for students and talent, changing demands and new methods of education are some of the factors that are forcing universities to re-examine their role, functioning and position both in their surrounding society and in the global arena.”[9]

Within this national environment, and with the interest and support of the Swedish government and the local Malmö community, Malmö University has a tremendous opportunity to evolve in a manner that focuses on its Urban University ethos, yet that also selectively builds its international reputation and attractiveness. Under its own terms, it might see itself as an emerging Urban New Flagship University.

The key is to further develop the internal academic culture and quality assurance practices that shape its larger mission; and to avoid the pitfalls of the race for global rankings or other misguided measures of productivity. In other words, my sense is that through Malmö University’s urban mantra, including research relevant to local and societal issues, will come a growing international reputation. Indeed, most international students are highly practical – most want to pursue disciplines and professional programs with the prospect of advancing a career. And faculty often wish to pursue research within the laboratory of urban settings.

In this essay, I have focused on the concepts of engaged scholarship and public service as one vital area that Malmö University is undoubtedly already pursuing to some extent. But to help shape the engagement activities of the university, perhaps there is no more important policy area than the expectations placed on faculty. Students, and administrative staff, play essential roles in helping to guide a university as an organization. But the key to any university’s mission and quality is the quality and expectations placed on academic staff. And, similarly, it is the internal academic culture of the institution itself, and its matching policies and practices, that will drive both quality and innovation. Ministries may push and cajole through laws and money. Yet these are not the determinants of the most productive and influential universities.

[1] Malmö University (2013). 2020 Strategic Plan.

[2] A faculty recruitment study at Harvard of more than 2,000 doctoral students and almost 700 first- and second-year faculty members at a sample of top American universities asked respondents to rank the importance of such factors as salary, location, chances of tenure, department quality, and institutional prestige when weighing different offers. Both groups ranked geographic location and quality of life as their first priority, followed by the ”work balance” between teaching and research. Salary and institutional prestige are ranked toward the bottom of the list. The tenure factor is ranked somewhere in the middle.

[3] See John Aubrey Douglass, The New Flagship University: Changing the Paradigm from Global Ranking to National Relevancy (Palgrave Macmillan 2016), and a follow-up book, John Aubrey Douglass and John H. Hawkins, Envisioning the Asian New Flagship University (Berkeley Public Policy Press, 2017).

[4] The Coalition of Urban Serving Universities including 35 public urban universities in the US: USU’s work centers on two reinforcing pillars: initiatives working to advance student success through innovation and initiatives aiming to achieve community transformation through partnerships. By collaborating across universities with shared challenges and functions, USU institutions can pilot, refine, and share the most effective practices to accelerate innovation across higher education.

[5] Robert Hollister (2013. “The Engaged University—an Invisible Worldwide Revolution.” Tisch College of Citizenship and Public Service.

[6] Mats Benner, Arthur Bienenstock, Sylvia Schwaag Serger, Anne Lidgard (2014). Combining Excellence in Education, Research and Impact: Inspiration from Stanford and Berkeley and Implications for Swedish Universities. SNS Forlag.

[7] As early as 1997, the higher education law of made interaction with surrounding society an official “third task” of Swedish institutions for higher education (HEIs). Yet most universities were slow to conceptualize how they might innovative to serve this larger purpose.

[8] Mats Benner, Arthur Bienenstock, Sylvia Schwaag Serger, Anne Lidgard (2014). Combining Excellence in Education, Research and Impact: Inspiration from Stanford and Berkeley and Implications for Swedish Universities. SNS Forlag.

[9] Emily Wise, Mårten Berg, Maria Landgren & Sylvia Schwaag Sergerwith Mats Benner & Eugenia Perez Vico. Evaluating the Role of HEIs’ Interaction with Surrounding Society: Developmental Pilot in Sweden 2013-2016. Vinnova (Swedish Government Agency for Innovation) and Lund University Report number: 978-91-87537-55-4.

Biography

John Aubrey Douglass is a Senior Research Fellow – Public Policy and Higher Education at the Center for Studies in Higher Education at the University of California – Berkeley and the author of the book, The New Flagship University: Changing the Paradigm from Global Rankings to National Relevancy.

Along with authoring a number of books, research projects he has founded include the Student Experience in the Research University (SERU) Consortium – a group of US and international major research universities, with members in China, Brazil, South Africa, the Netherlands and Russia.

He is also the editor of the Center’s Research and Occasional Paper Series. He also sits on the editorial board of international higher education journals in the UK, China, and Russia, and serves on the international advisory boards of a number of higher education institutes.

He has been a visiting researcher at the Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung, a visiting professor at Amsterdam University College, at Brazil’s Universidade Estadual de Campinas, at Sciences Po in Paris and a visiting research fellow at the Oxford Center for Higher Education Policy Studies.